Maynard's chapter concerns photographic detail, and the relationship it has to "fidelity." As a way of beginning, we should say that "fidelity" is, for Maynard, a way of avoiding the word "truth"--a loaded word in scholarship if there ever was one--but also a way of making the idea of truth concrete and practical with respect to art. The practical value of the word "fidelity" is that it calls to mind the notion of a proposition's accordance to a particular state of affairs--correctness. In this case, "photo fidelity" refers to the degree to which a photograph accords with what its viewers believe is being depicted. As you can tell, this terminology doesn't clean up that mess.

But there's another mess Maynard wants to clean up first: the notion that photography has changed our perceptual habits. This was put forward by William Ivins, who was the director of prints at the Metropolitan Museum in New York during the early 20th century, and who stated that people began to "see photographically" during the end of the 19th century, once photographs became easy for the amateur to make, and had begun to appear in print every day around industrializing world. Maynard also notes that this has been restated by many over the course of the 20th century, including Susan Sontag, an important thinker during the second half of the 20th century who wrote an important book called On Photography. But Ivins and Sontag aren't clear about what "seeing photographically" means, which forces Maynard to provide that clarity for us. Does it mean that photographs have enlarged our vision, or narrowed it? Supersaturated it, or desaturated it? Caused us to see things as if in a frame? We can think of many aspects of photography that could, in theory, reform our vision, but Maynard thinks it has not, at least in the way Ivins and others suggested.

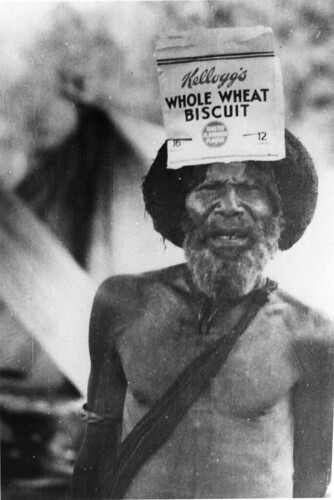

The story from New Guinea of the peoples there going wild for photography, film, and recorded voices is usually told to underscore a claim that photographic seeing--in this limited case, understood as the ability to read a photograph--must be learned. Despite how naturalistic a photograph appears to us, it is anything of the sort for those who have not grown up with them. However, Maynard points out that the shock wasn't so much the photograph, but the indigenous peoples seeing themselves. This may be overly humanistic, this idea that it's embarrassment or fear that caused their hysterical reactions (like our aversion to our own photographed likeness) and not the technology itself. But there is surely something to it, particularly if they had never seen themselves in a mirror, as was suggested. In any case, what Maynard wants to argue is that since we don't need much effort or training to recognize the content in photographs and insert them into our cognitive repertoire, there's not much chance they could, in return, affect our day-to-day perceptual habits.

There's something attractive about Maynard's argument, as much as we still might like the science-fictiony idea that technology is changing how our bodies work. If we don't have to change much to understand the photograph, then the photograph can't really change us. Language, if anything, augments our cognition far more than photographs or images ever could. Our culture and every culture is built upon language--money, corporations, science, government, and marriage would be impossible without language, and surely possible without images--and without language who knows what the content of our thoughts would be like. Having said that, does Maynard really take into consideration all the relevant aspects of photography that could reorient our perceptions of the world, in order to sufficiently diffuse the claim?

The one aspect that Maynard considers in detail is detail, since that's what impressed nearly everyone who saw the first photographs. The daguerreotype especially--the amount of detail that process recorded (as opposed to the first calotype paper-negative process) led at least one commentator to write that it was often beyond the ability of art to match its effects. This is a surprising claim, not so much for its content but for the fact that it was even said. The idea that the photograph could ever be superior to traditional arts was dangerous to voice in public; photography's appealing ease of use has always been its most embarrassing trait within the arts. In any case, whether or not the photograph contained more detail than a painting depends on too many factors to be tested, but certainly no painting ever contained as much detail in such a small area--the daguerreotype was only a few inches long. Of course, even this distinction needs qualification, for as Maynard is eager to note, there is an important difference between the detail of paintings and the detail of photographs. Paintings contain infinite detail, but this infinity is mostly the detail of paint, and not of the depicted subject, but as such it is also understood as part of the painting's expressive repertoire. By contrast, the more grain we see in a photograph, the less detailed we say it is. Much of the maddening degree of detail we see in photography is the result of our imagination.

But there are two sides to the detail question, especially as it relates to the "fidelity" of the photograph to the world from which it was taken. On the one hand, a photograph contains more detail than any single perception of ours can take in. On the other hand, as many commentators have noted, so much of this detail is incidental, and it often unbalances the composition of a photograph, or makes it messy. Let us consider this photograph from the early part of the 20th century:

It's a crime scene photograph, as you may have guessed. While the view and subject matter are weird enough to make the photograph interesting forever, the photographer clearly hasn't tried to clean up its mess of detail. In fact, it's explicitly his job not to. And even though this photograph would not have been viewed as an autonomous picture, as art, in its time--detectives and prosecutors would have appreciated the photographer's inclusion of the mess behind the head and likely missed the jokey impalement of the ladder, and the guillotiney character of the anonymous machine against the wall--it's worth noting that the haphazard composition of a sordid mystery that would have been it unpalatable to aesthetes of the 19th century would become the goals of many 20th century art photographers, who believed that a messy photograph only heightened the viewer's fear that what they were seeing was real. How cultivating messes made something appear more real is another important matter to ponder another time. Here's another picture of the same crime scene. It would probably be less appealing if we'd never heard of God.

As Maynard notes, the the fact that photographic detail, right from the beginning of the medium, was seen as riches, embarrassing, or both means that we can't separate detail from aesthetics--one would intuit this immediately perhaps, but it's it's important to keep in mind. Just because we recognize information doesn't mean that we're able to make good sense of it. This means something interesting with respect to truth and photography. If the objects described by a photograph aren't organized in a "legible" way--that is, if they aren't depicted well--we won't be able or inclined to interpret them, to "read" them, and make meaning from them. Please understand that I'm not using these terms of literacy literally--I don't want you to think that we "read" photographs, that much for sure. They are not based on codes, though many have tried to say they are. There are too many different pictures for that. The point, though, is that in order for a photograph to even be a proposition that can accord with a state of affairs, its information, its content, doesn't have a meaning or evoke an experience until it has a form, or otherwise an editorial context--something to indicate to us how to access its contents. A mess of details is simply a mess, even if it is intricate. Here is one of Peter Henry Emerson's pictures, which strive for a perfect balance of infinite detail.

Let's compare this to the first of the crime scene photographs above. In Emerson's picture (British, 1880s), the larger elements are given space to breathe on their own, hardly the case with the crime scene shot. In Emerson's picture, the mass of incidental grass detail doesn't compete with the man it surrounds, for the light catches on to his bright shirt, and the water in the marsh marks his place on the picture's ground. Emerson is moreover careful not to describe anything prominently that we can't identify; we would hardly say this of the crime scene photograph. But both pictures make a metaphorical threat out of their machines--blades and gravity over the unsuspecting subject--a suggestion that really only makes sense with pictorial seeing. The difference between the two metaphors, though, is that while the crime scene's seems to be a fortuitous juxtaposition by virtue of its haphazardness, Emerson's delicate, precise arrangement makes his metaphor seem like it's contributing to an allegory about birth (the tree), work (the subject), and death (the decaying, threatening windmill). I hope you all see that the allegory, whatever it is exactly, is more complicated than this. I will leave it to you to ponder.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment